“I’m not a risk taker” – the US BASE jumpers’ perception of their own risk tolerance

There was supposed to be an article about skydivers’ perceptions of their propensity to take risks, but it turns out that people in the USA are a bit different than in Poland. Intercultural differences?

Skydiving is undoubtedly a risky sport* but it can be practiced in a more or less safe way. Under what conditions do you jump, on what parachute, what do you do in the air, with whom … – these are some of the decisions that each skydiver must make and which affect how much risk a given jump will involve.

Some people often choose to take higher risks (their risk tolerance is high, we can say that they are higher risk takers), while others are more cautious (they have low risk tolerance).

Jeremy Sieker, a skydiver and medical student at the University of California, conducted a study to answer the question of how skydivers see their risk tolerance compared to others. Do they consider themselves risky or rather cautious jumpers?

194 skydivers took part in the study, 87% of whom are men.

If everyone had an accurate view of their risk tolerance, the answers would be expected to be normally distributed. Most people should answer that their risk tolerance is average, the answers “lower” and “higher” should be given less frequently, more or less the same often, and the most rare answers should be “very low risk” and “very high risk, which should also be given about the same number of times.

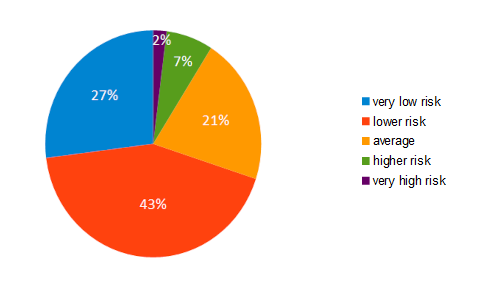

It turned out, however, that the results were very different from this distribution. As many as 70% of the survey participants replied that the risk they take is lower or very low compared to that taken by average jumpers.

Only 9% admitted that they are higher risk-takers than the average jumpers. Interestingly, all participants of the study practice BASE jumping (jumping from fixed objects, which is commonly considered the most dangerous type of parachute jumping).

Of course, some may be right about their lower risk tolerance, but this distribution of responses indicates that many people must be wrong.

The author of the study also asked participants how often they prepare an emergency plan by jumping in a new place. If they are concerned about their safety, you’d expect that they should always have one. It turned out that only 18% of BASE jumpers always do them.

From the results obtained, it can be concluded that probably many people think of themselves as safe BASE jumpers, but in fact they do not analyze their behavior, how they prepare for jumping and how much risk they take. Perhaps some of them are not even aware that they are taking risky actions while jumping.

Intercultural differences?

Jeremy Sieker, reflecting on the possible reasons for such results, points out that perhaps less risky people were more willing to complete the survey. This cannot be ruled out, but in my opinion what we see here is superiority bias.

The superiority bias, also known as the illusory superiority or the above-average effect, is a phenomenon very widely described in psychology. A lot of research has been done on this phenomenon, and no matter what the participants are asked about – whether about their driving skills, intelligence, leadership, sense of humor, ability to interact with people, or something else – it always turns out that most consider themselves in this respect as better than average.

As Jeremy Sieker rightly pointed out, the safety aspect penetrated deeply through the skydiving environment. Caring for safety is seen as a positive trait and being a risk taker is not something to brag about in the company of skydivers. This could cause many people to see themselves as safer, that is better in this respect than other jumpers.

Importantly, research on the superiority bias was conducted mainly in the USA. The ones that were carried out in Eastern culture indicate that this phenomenon does not occur there, which I wrote about in the article Cognitive biases in different cultures.

What makes these cultures different is the dimension of individualism-collectivism. It indicates whether a person perceives himself more as “me” or “we”. In individualistic cultures, the individual matters and people mainly care about themselves and their immediate family. On the other hand, in collectivist cultures, the interests of the group to which they belong are more important to people than their own. Highly individualistic societies include USA, Canada, Australia, UK. Highly collectivist are Asian countries (for example China and South Korea), but also Belarus and Ukraine. Poland is in the middle, but more towards individualism.

Interested in the results of Jeremy Sieker, I conducted a similar research among Polish skydivers to check if consistent results would be obtained.

On the groups and on my Facebook profile, I posted a questionnaire, in which at the beginning I put an explanation that read: “Risk tolerance determines our level of acceptable risk. Some people have higher risk tolerance and therefore are inclined to engage in riskier activities. For others, the level of risk that they are willing to accept, ie take, is lower. ” Then I asked the question, “Assess your risk tolerance compared to other skydivers.”

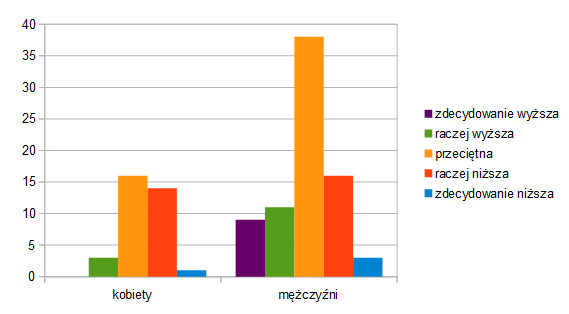

112 people answered the questions, 69% of which were men.

The results were not as spectacular as in Jeremy Sieker’s research. A slight shift towards lower risk can be noticed, because 49% rated their risk tolerance as average, 30% as rather lower or definitely lower, and only 21% as higher or definitely higher, but in general the distribution of results is close to normal.

When broken down by gender, it can be observed that women reported relatively more often that their risk tolerance was lower than average. It is difficult to say whether some were wrong in this regard, or whether they actually accept less risk than men.

Perhaps the difference in the results between the research conducted in the USA and in Poland is due to intercultural differences. In Poland, due to lower individualism, the effect of being better than average may not be so intense.

Other possible explanations

Perhaps the number of parachute jumps is important. Although neither in my study, nor in Jeremy Sieker, the number of jumps did not correlate with the perceived risk tolerance, but there are significant differences in the studied groups. In his study the median number of jumps was 700 and in mine it was only 158.

Or maybe BASE jumpers are a special group? In my study, only a few people answered the “yes” to the question whether they do BASE jumping, their answers were different and the small sample does not allow any statistical analysis.

As skydivers, we don’t want to be perceived by others or ourselves as risk takers, so perhaps the high risk they take is prompting many of them to deny risk more, saying that what they do is not all that dangerous. In my opinion, the claim that driving to a dropzone by car is more risky than the skydives, which I have heard many times from other skydivers, is a symptom of such a denial. Perhaps it is more pronounced with BASE jumpers.

The methodology can also play a role. Jeremy Sieker did not quote exactly what question he asked the participants, and sometimes a slight difference in the content can lead to different results.

The results of both studies certainly indicate that it is worth replicating psychological research and that certain conclusions should not be drawn from just one small study, nor should we generalize the results of a study conducted on one population to other populations.

* Many skydivers deny it, but I have no doubt that it can be classified as risky sport.

References

Author: Maja Kochanowska

Add comment