Brain images make the article seem more reliable

Even if the article does not make much sense, inserting a photo of the brain scan into it makes the article more “scientific” and credible for readers. The content that sounds “neuroscientific” is also relevant to readers. Phrases such as “brain scans have shown” and referring to concepts in this field of science cause the text to be better evaluated, although in reality it can only sound wise.

Brain images and perception of text in the field of neuroscience

Research on the impact of brain images on the perception of an article on neuroscience was conducted by McCabe and Castel (2008). In their first study, they presented study participants with articles summarizing the results of fictitious research in the field of neuroscience and asked them to answer the questions about how much they agreed with the following statements: “The article was well written”, “The title was a good description of the results”, “The scientific reasoning in the article made sense”. In fact, the scientific reasoning made no sense. For example, the article “Watching TV is Related to Math Ability” described the results of fictitious research, according to which watching TV increases the activity of the temporal lobe, as well as solving mathematical problems. The conclusion was that watching TV improves math skills. Of course, this is an unauthorized request. It is impossible to draw such conclusions on the basis of such data, although in fact many journalists draw such conclusions, and people believe them because they saw a brain image in the article ;)

The texts that McCabe and Castel prepared had three versions: with brain images showing the activated temporal lobe, with charts presenting the results and without any graphics. Each study participant received one of these versions for reading.

It turned out that there were no differences between people who read the article without graphics and those who read the article with charts. Those who read the article in which the brain scans were placed, however, assessed the article in terms of credibility much better.

In another of their experiments, researchers presented the study participants not fictitious texts, but real, downloaded from the BBC website. This article had no errors in its conclusion. Study participants were asked if they agreed with the conclusions presented in the article and, similarly to the first experiment, people who read the article in which the brain image was found were more likely to agree with this article than people who read the article without such a picture .

“Neuroscience” texts in psychology articles

Other interesting studies showing how “neuroscience” affects text evaluation were conducted by Weisberg and colleagues (2008). The researchers gave the participants to read texts on various psychological phenomena and explanations of the phenomena they were to assess (to what extent these explanations are satisfactory for them). The explanations were presented in four forms and each participant of the study was to assess one of these explanations. They were either “good”, that is meaningful and consistent with scientific knowledge in this field, or “bad”. “Bad” explanations only presented the phenomenon described earlier in other words, but did not explain anything. The second feature that the explanations differed were neuroscientific sentences woven into the content.

The table below shows one of these sets of explanations. To facilitate observing the differences between them, the “neuroscience” content is in bold. The explanations concerned the phenomenon of “the curse of knowledge” about which the study participants read the text (the phenomenon is that if we have some knowledge, it seems to us that others also have it, for example, 50% of Americans know that Hartford is the capital of Connecticut, but those of those 50% asked about how many people think they know it indicate an average of 80%).

| Good Explanation | Bad Explanation | |

| Without Neuroscience | The researchers claim that this “curse” happens because subjects have trouble switching their point of view to consider what someone else might know, mistakenly projecting their own knowledge onto others. | The researchers claim that this “curse” happens because subjects make more mistakes when they have to judge the knowledge of others. People are much better at judging what they themselves know. |

| With Neuroscience | Brain scans indicate that this “curse” happens because of the frontal lobe brain circuitry known to be involved in self-knowledge. Subjects have trouble switching their point of view to consider what someone else might know, mistakenly projecting their own knowledge onto others. | Brain scans indicate that this “curse” happens because of the frontal lobe brain circuitry known to be involved in self-knowledge. Subjects make more mistakes when they have to judge the knowledge of others. People are much better at judging what they themselves know. |

The insertion of information about the brain did not add anything essential to the explanation. “The frontal lobe is involved in self-knowledge.” OK, so what?

Interesting in this study is that it was done on three groups of participants. The first were “ordinary” people (the authors of the study assumed that they do not have knowledge in neuroscience), the second group was students attending classes in neuroscience, and the third group were specialists in neuroscience.

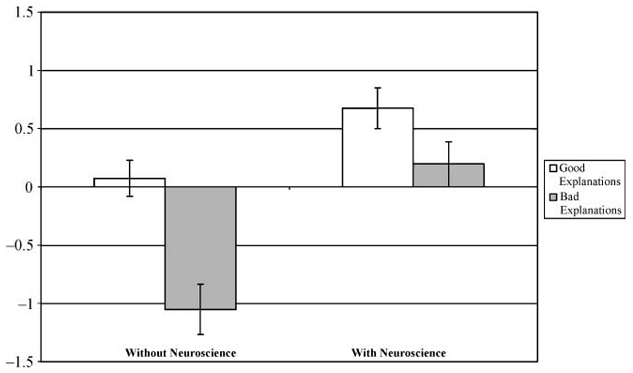

Group 1 – “Novice”

People who did not have knowledge in neuroscience assessed good explanations as equally satisfactory, regardless of whether they contained “neuroscientific” information or not. In the case of poor explanations, however, the “neuroscientific” content significantly influenced their assessment .

Stupidity without neuroscience will not be well received by readers. But if stupidity with neuroscience concepts is added to such stupidity, such a text will be considered wiser :)

Group 2 – “Neuroscience students”

It would seem that students attending classes in neuroscience should be resistant to the effect of “neuroscientific content”. They have knowledge of the subject, so they should be able to assess whether such content makes sense or not. Really?

The chart below presents the results of this group of respondents.

As you can see, students rated good explanations poorly if they had no neuroscience content. Neuroscience content meant that both good and bad explanations were rated better. Students who enrolled in classes in neuroscience are probably so fascinated by this field that any text that contains some concepts from neuroscience is perceived by them as good, and every which does not contain such concepts is bad in their opinion. Interest in neuroscience and learning of this field of science, however, does not make them able to look at such content with a critical eye.

Interestingly, the authors of the study in students conducted this experiment twice: at the beginning of the semester and at the end. However, there were no differences between the results. The whole semester of neuroscience did not teach them a critical look at neuroscientific content.

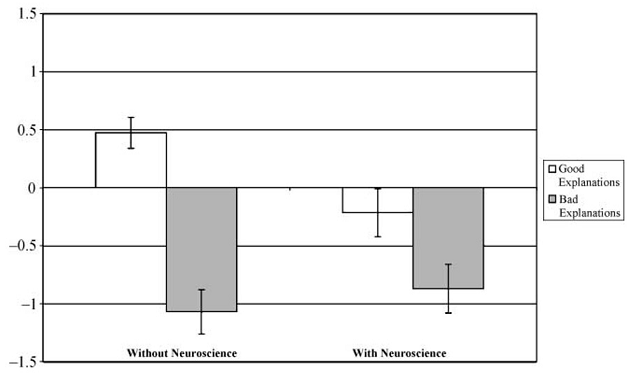

Group 3 – “Neuroscience specialist”

This group includes people who have completed or were in the course of master’s or doctoral studies in neuroscience, cognitive psychology or other closely related fields. Can such people look with a critical eye on neuroscientific content?

Even with a very critical ;) Specialists assessed even good explanations as unsatisfactory if they contained neuroscience content. Several of them were asked after the study why they assessed the explanations presented to them in this way. It turned out that these people are so sensitive to the unnecessary and senseless use of neuroscience concepts that inserting such concepts into the content resulted in a decrease in the overall assessment of such content.

I think it is worth knowing about the phenomena presented in these studies so as not to be charmed by nice “specialistic” pictures and “wise” concepts. If you read on some popular or general science portal on neuroscience research and consider this to be a credible scientific text, I advise you to read it again and wonder if it really is or just looks like it.

I hope you found my text interesting and credible, because it contains such information, and not because I have inserted brain images ;)

References

- McCabe, D., Castel, A. (2008). Seeing is believing: The effect of brain images on judgments of scientific reasoning. Cognition 107, 343-352. (pdf at antoniocasella.eu)

- Weisberg, D. i in. (2008). The Seductive Allure of Neuroscience Explanations. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20(3), 470-477. (text at nih.gov)

Author: Maja Kochanowska

Add comment